Organs-on-Chip-as-a-Service: A proposal bridging cloud services and scientific experiments

Abstract

Technological advancements enable delicate and complex experiments on small-scale devices, such as organs-on-chips, improving and accelerating research. At the same time, an ever-increasing diversity of hardware platforms is accessible via cloud services. This perspective article describes our vision for the future of organs-on-chips. We present the main idea behind organs-on-chips as a cloud service, a brief description of the proposed infrastructure, and some applications.

Keywors

Organs-on-chips, tissue-as-a-service, cloud computing, neuroscience, experiments

Introduction

Organs-on-chips (OoCs) are small-scale devices that sustain living tissue and emulate human organs. Recently, their importance in precision medicine, pharmaceuticals, and basic science has been highlighted by many researchers. More precisely, an OoC is a microscopic device that consists of multiple chambers lined with human (or other biological) tissue [1, 2, 3]. OoCs have a relatively low cost to build, permitting the manufacturing of devices at scale [1, 4]. Another significant advantage of OoCs is the precision they offer. Researchers can deal directly with human tissue without relying on crude, and inaccurate animal models for human diseases or degenerative disorders [5]. Furthermore, by removing lab animals from experiments, we also satisfy a moral obligation: not having to harm or put an animal to death.

Current technology could be used to build semi-automated farms of OoCs and use them as a cloud service, like Amazon Web Services (AWS) [6]. Here we describe our vision for cloud infrastructures that provide remote access to OoCs. More precisely, warehouses can host racks of OoCs along with servers and GPU/accelerator clusters. We will refer to this service as CloudLab. An infrastructure like CloudLab will provide all the necessary means for running, managing, and monitoring systems biology experiments remotely.

The infrastructure

CloudLab’s OoCs will be hosted in incubator-like rack servers. Using existing data center infrastructure, communication protocols, like Ethernet, enable remote access to the OoC. Furthermore, systems of microcontrollers and sensors in the servers will monitor the OoCs in real-time and at all times. All necessary environmental parameters of the OoC, such as oxygen/carbon dioxide levels, humidity, and temperature, will be automatically controlled. Sensors will provide real-time information about tissue health and report the hardware’s condition. All previously mentioned parameters and potentially more will be stored in a data log at different points in time.

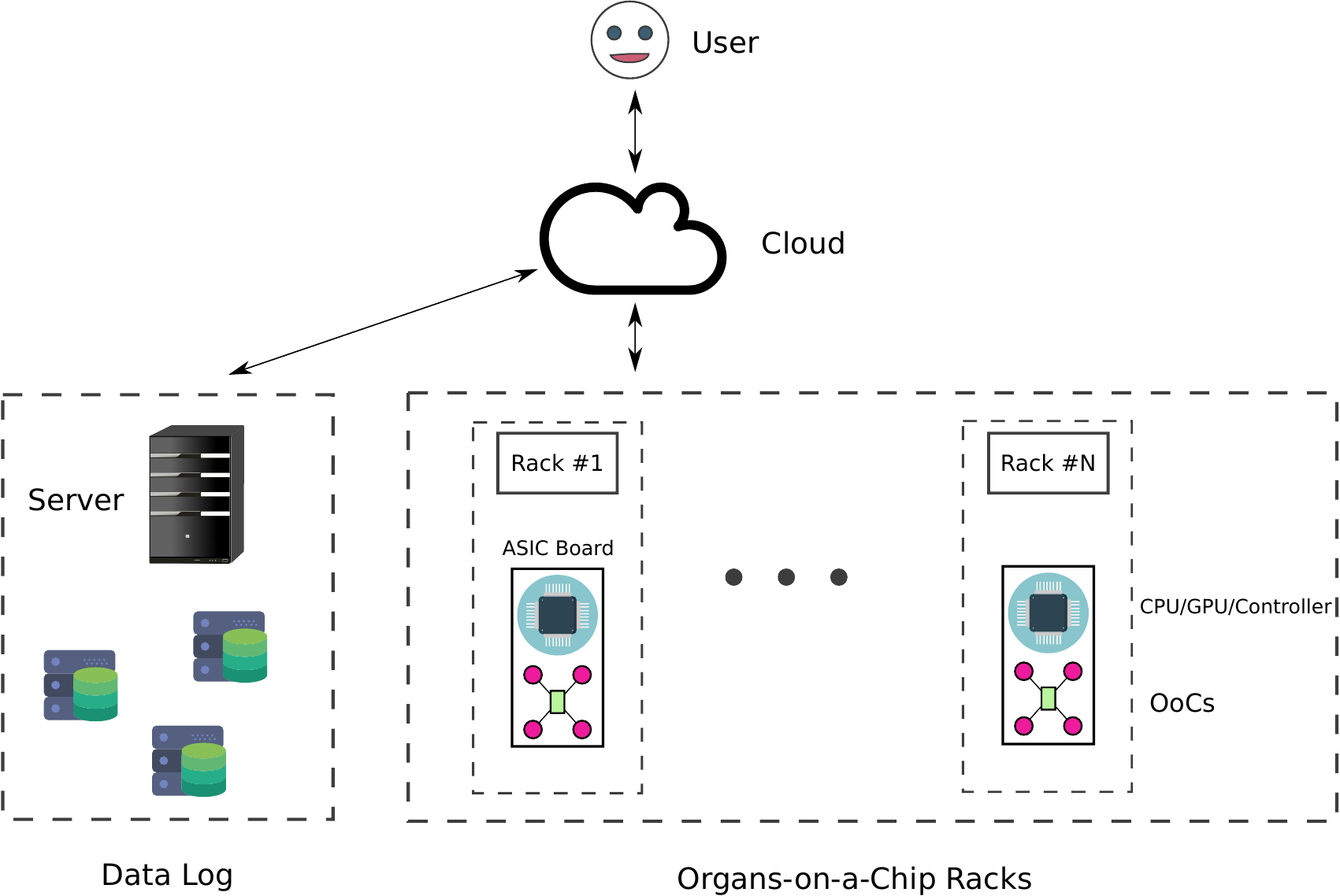

Figure 1. CloudLab Schematic.This figure shows an oversimplified schematic representation of how CloudLab operates. A user signs up and gets an account to log in on the central server (distributor). Once connected to the server, they can use a web interface or a Unix terminal to set up and run experiments on CloudLab using the provided organ-on-chip devices. Each rack provides multiple OoCs and CPUs/GPUs. However, the user can combine OoCs from different racks and run experiments in parallel or distribute massive experiments to obtain results faster.

The service will provide users with tissue instances (TIs), which function like virtual machines in familiar cloud services. TIs are intended to enable remote access to the OoCs in the form of a web interface or a terminal-based shell named labsh. Users can execute labsh commands in the TI’s terminal (or in a web interface) to retrieve tissue sample data in real-time or from the TI’s data log. The data log can be implemented by the provider using a time series database, like InfluxDB.

CloudLab must guarantee uninterrupted TI access and smooth operation. To this end, besides all conventional hardware failsafe mechanisms, CloudLab will provide sophisticated tools for monitoring the health of living tissue. Machine learning and traditional control algorithms will be responsible for monitoring the health of the tissue on OoCs. For instance, autoencoders can perform well in detecting anomalies in time series data [7]. In CloudLab, autoencoders could be hardware malfunction or tissue damage detectors since all necessary environmental data will be stored in the data log. The application of machine learning in CloudLab will not be limited to autoencoders. Machine learning algorithms can also be used to predict the lifespan of biological tissue by observing actual data from the OoCs. Moreover, they can be trained to prevent experiment failures and tissue damage.

CloudLab will be similar to existing cloud services, like AWS. Hence, users will sign up for an account on the CloudLab service. Once granted access to the service, one can instantiate new TIs and run experiments remotely. The user will be responsible for determining the number of devices required and the types of cells or organs they would like to use in their experiments. Assignment algorithms (e.g., the Hungarian algorithm) automate and assist in assigning resources and devices to each user at any given time. Automation at that scale is quite helpful since one user might have to use multiple devices in multiple racks. Alternatively, another user might need only one device. Therefore, assignment and concurrency algorithms are in place to ensure that all users can conduct their experiments, regardless of scale.

Figure $1$ is a schematic detailing the proposed CloudLab infrastructure. The user can access all the provided services by logging in to a server. Users can demand as many racks (or OoCs) as they would like. The system gathers all the necessary information and assists the users in setting up their experiments. The users can monitor their experiments as they are executed and collect results in real-time. The experiments’ parameters and conditions are constantly monitored, and all the data are stored in a data log. The figure shows an oversimplified structure of racks, where OoCs coexist with boards equipped with CPUs, GPUs, microprocessors, and microcontrollers.

Safety and Security in CloudLab

Furthermore, fail-safe mechanisms such as real-time controllers and sanity checks will validate the input from the user so the devices remain within their limits of operation. These protective mechanisms will also prevent any unethical use of the equipment (e.g., bioterrorism). Handling hazardous material or conducting experiments that involve toxic substances are important issues for CloudLab. These problems require a two-fold solution. Firstly, the racks that host the OoCs must be hermetically sealed as the first line of defense. Secondly, to ensure the safety of all personnel and the facility itself, we propose to dedicate a biosafety level $4$ area within the warehouse to host all dangerous experiments. Academic institutions and pharmaceutical companies that use hazardous materials may receive written clearance for conducting more complex experiments.

Applications

Neuroscience

Neuroscientists can study the effects of a drug on a specific group of neurons (one OoC device) throughout the brain and how it affects other groups (other OoC devices connected to the affected one) of neurons with different cytoarchitectures. They can read electrophysiological signals from one tissue sample and forward them as driven stimuli to another. To this end, parallel experiments on different OoCs can interact with each other via an address event representation (AER) protocol that conveys information in a bandwidth-economical way from one device to another [8]. This approach can be used to approximate larger, continuous pieces of tissue. Medical device researchers can test new invasive treatments such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) [9], cardiac pacemakers, or any other implant device without relying on animal models. This would be done by hosting relevant tissue, like neural tissue, on microelectrode arrays (MEAs) to enable users to deliver electrical test sequences remotely. They will have the opportunity to investigate how their methods affect the tissue and other structures, such as blood vessels, in a realistic human model using CloudLab. These experiments could scale up and accelerate the invention of new therapeutic methods. Furthermore, CloudLab offers the means to scientists to examine the secondary effects of their proposed treatments and not only the immediate effects. For instance, an invasive method such as deep brain stimulation might cause inflammation and thermal damage. In that case, researchers can use tissue in OoCs to test the correct currents and voltages and calibrate all necessary parameters for a stimulation algorithm (e.g., PID controller gains). Moreover, they can perform identical stimulation sequences on a diverse set of tissues without relying on crude in vitro or in vivo animal models [10, 11].

Pharmaceutical research

Researching new drugs can be tedious and involve complex procedures requiring time and money. CloudLab allows researchers and companies to conduct thousands of experiments in parallel. Therefore, researchers could test their hypotheses or new compounds en masse. Researchers can configure brute force attacks in search of pharmaceutical compounds for specific diseases. Compounds will be able to be synthesized from a set of precursors using a rack-scale, remotely-accessible chemical plant provided by CloudLab. Therefore, researchers will be able to obtain valuable results in less time than with the present technology since thousands of simultaneous experiments can be run.

Another potential application for CloudLab is orphan drug development for rare diseases. Drugs usually undergo clinical trials after being successfully tested on animals in the lab (pre-clinical trial). A clinical trial consists of three to four phases, the details of which are out of this article’s scope. Phase III of clinical trials is the most costly (over $60$% of clinical trial costs) [12]. Additionally, orphan drugs may not even make it to phase III trials [13]. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that orphan drugs may have a more significant share of their costs concentrated in pre-clinical trials, making them a suitable niche for CloudLab, which could offer a platform for rapid development and testing of orphan drugs on OoCs of human tissue.

Machine and Deep Learning

CloudLab is a platform that allows and encourages scientists to use machine/deep learning (ML/DL) algorithms in their experiments [14, 15]. The infrastructure consists of servers equipped with GPUs and other accelerators to enable immense computational capabilities. Therefore, researchers can combine machine learning algorithms on-the-fly to analyze their experimental raw data. Moreover, machine learning can also facilitate and increase research quality when researchers combine ML/DL with OoCs. For instance, deep neural networks will operate and communicate with neural tissue living in OoCs. This kind of research can shed light on how the brain and neural networks alike work [16].

Furthermore, computer vision algorithms provide real-time, high-fidelity image analysis and processing [17]. The OoC racks will be equipped with cameras and thus be capable of analyzing data in real-time using computer vision algorithms. Furthermore, small form factor microscopes can be embedded in the racks and offer more options to researchers. All the mechanisms above will improve and facilitate OoC experiments by allowing researchers to automate many complex tasks requiring much human labor and time.

Education and Training

CloudLab facilitates and promotes basic research since every researcher can access a virtual lab from anywhere in the world. Researchers have access to state-of-the-art equipment and can conceive, devise, set up, and run their experiments. Many research laboratories in small universities or developing countries cannot afford to buy experimental equipment. By granting them access to CloudLab, they can consequentially contribute to the field at a substantially lower cost.

Moreover, CloudLab will also be an excellent educational tool for undergraduate, graduate, and high school students. Professors could get access to CloudLab and set up experiments for their students, and even undergraduate and graduate students could set up their experiments for conducting research or training. CloudLab also offers students a means to safely run experiments involving hazardous materials. Moreover, students in biology, medicine, chemistry, and other life-science disciplines will be able to run experiments with great ease. They will not have to rely on their professors’ or institutions’ budgets to acquire lab equipment. They will only have to sign up for the CloudLab service.

An example of how to use CloudLab in education is given by Elena. Elena is a software engine for developing educational games. It was originally designed to provide an interface between students and a CloudLab-like service [18]. For instance, some of the experiments provided by Elena focus on testing the melting point of different substances, like gallium. The thermoelectric cooling demos in the Elena repository document an attempt to build a device that makes melting point experiments remotely accessible. Users would play through a trivia game and encounter a bonus round that would involve setting the hot plate’s temperature and identifying the material based on its melting point. This bonus round game was originally intended to involve the remote hardware. Thus, frameworks like Elena could be used to build games that make CloudLab apps more engaging in a classroom setting.

Economic Benefits

From an economic standpoint, pharmaceutical applications are the most promising. In some instances, the exploding cost of pharmaceutical development might be better managed by OoC-centric remote lab technologies than existing approaches. An interesting and worrisome fact about clinical trials is that less than $10%$ of pharmaceuticals that begin phase I trials will become products. Furthermore, over half of pharmaceuticals that make it to phase III fail to reach the market. These failures cause the cost per new drug to skyrocket to nearly $1 billion [19]. OoCs and CloudLab can mitigate clinical trial problems. OoCs are low-cost, more accurate models of human organs and perform better than animal models in pre-clinical trials. Thus, the use of OoCs will likely lead to higher trial success rates and thus to cheaper, more effective, and safer therapies (e.g., drugs). CloudLab could improve even further that endeavor for reasons we already mentioned above. It allows researchers to try many different approaches in parallel (i.e., brute-force attacks) and receive the results of their experiments much more quickly.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we briefly described how a relatively new technology, organs-on-chips (OoCs), can be used in a cloud service, facilitating research, education, and the rapid development of pharmaceutical compounds. We call this service CloudLab and have described some of its essential functions and operational capabilities. CloudLab is an equivalent of AWS for life sciences, and it will provide researchers the ability to conduct state-of-the-art research in many scientific fields. Technologies like CloudLab will enable substantially faster and more accurate scientific research results.

Cited as:

@article{detorakis2022cloudlab,

title = "Organs-on-Chip-as-a-Service: A proposal bridging cloud services and scientific experiments}",

author = "Georgios Is. Detorakis and Roman Parise",

journal = "gdetor.github.io",

year = "2022",

url = "https://gdetor.github.io/posts/cloudlab"

}

References

- Donald E Ingber. Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling, drug development and personalized medicine. Nature Reviews Genetics, pages 1–25, 2022.

- Alex Ede Danku, Eva-H Dulf, Cornelia Braicu, Ancuta Jurj, and Ioana Berindan-Neagoe. Organ-on- a-chip: A survey of technical results and problems. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 2022.

- Qirui Wu, Jinfeng Liu, Xiaohong Wang, Lingyan Feng, Jinbo Wu, Xiaoli Zhu, Weijia Wen, and Xiuqing Gong. Organ-on-a-chip: Recent breakthroughs and future prospects. Biomedical engineering online, 19(1):1–19, 2020.

- Chak Ming Leung, Pim De Haan, Kacey Ronaldson-Bouchard, Ge-Ah Kim, Jihoon Ko, Hoon Suk Rho, Zhu Chen, Pamela Habibovic, Noo Li Jeon, Shuichi Takayama, et al. A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2(1):1–29, 2022.

- Pablo Perel, Ian Roberts, Emily Sena, Philipa Wheble, Catherine Briscoe, Peter Sandercock, Malcolm Macleod, Luciano E Mignini, Pradeep Jayaram, and Khalid S Khan. Comparison of treatment effects between animal experiments and clinical trials: systematic review. Bmj, 334(7586):197, 2007.

- Sajee Mathew and J Varia. Overview of amazon web services–aws whitepaper, 2021.

- Chunkai Zhang, Shaocong Li, Hongye Zhang, and Yingyang Chen. Velc: A new variational autoencoder based model for time series anomaly detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.01702, 2019.

- Francisco Gomez-Rodriguez, Rafael Paz, Alejandro Linares-Barranco, Manuel Rivas, L Miro, Saturnino Vicente, Gabriel Jimenez, and Ant ́on Civit. Aer tools for communications and debugging. In 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, pages 4–pp. IEEE, 2006.

- Joel S Perlmutter and Jonathan W Mink. Deep brain stimulation. Annual review of neuroscience, 29:229, 2006.

- Junhee Seok, H Shaw Warren, Alex G Cuenca, Michael N Mindrinos, Henry V Baker, Weihong Xu, Daniel R Richards, Grace P McDonald-Smith, Hong Gao, Laura Hennessy, et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(9):3507–3512, 2013.

- Rafael Franco and Angel Cedazo-Minguez. Successful therapies for alzheimer’s disease: why so many in animal models and none in humans? Frontiers in pharmacology, 5:146, 2014.

- Asher Mullard. How much do phase III trials cost? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 17(11):777–777, October 2018.

- Kavisha Jayasundara, Aidan Hollis, Murray Krahn, Muhammad Mamdani, Jeffrey S. Hoch, and Paul Grootendorst. Estimating the clinical cost of drug development for orphan versus non-orphan drugs. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 14(1), January 2019.

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553):436–444, 2015.

- Daniel LK Yamins and James J DiCarlo. Using goal-driven deep learning models to understand sensory cortex. Nature neuroscience, 19(3):356–365, 2016.

- Neil Savage. How AI and neuroscience drive each other forwards. Nature, 571(7766):S15–S15, 2019.

- Erik Meijering. A bird’s-eye view of deep learning in bioimage analysis. Computational and structural biotechnology journal, 18:2312–2325, 2020.

- Roman Parise and Georgios Is. Detorakis. Elena: Open source javascript game engine for educators. Submitted to JOSE, 2022.

- Olivier J. Wouters, Martin McKee, and Jeroen Luyten. Estimated research and development investment needed to bring a new medicine to market, 2009-2018. JAMA, 323(9):844, March 2020.